Memoir traces friendship with Bernardin

|

This review first appeared in the American Reporter in 1998.

The late Joseph Bernardin was one of those rare religious leaders whose influence and voice transcended his own flock.

To be sure, not all cared for the late archbishop of Chicago and Cardinal of the Catholic Church. Doctrinaire Democrats were put off by his quiet insistence that we recognize the taking of life inherent in abortion and euthanasia. Ideologues on the right were discomfited by his steadfast opposition to the death penalty and public recognition of the humanity of illegal immigrants and the poor.

But perhaps because of these unpopular stands, Bernardin also earned the quiet admiration of people of all faiths – and no faith at all. Like Mother Teresa and the Dalai Lama, Bernardin's moral courage was also the source of his moral authority.

A new memoir of Bernardin gives a friends-eye view of this extraordinary man. As a young priest in the 1960s, Eugene Kennedy met Bernardin while serving on various U.S. conferences created to adopt the new teachings of Vatican II. In those heady, hectic days of tumult and controversy, a friendship was forged – a friendship that lasted until Bernardin's death from cancer in the autumn of 1996.

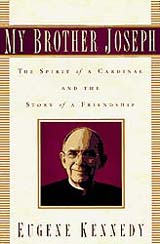

Kennedy's "My Brother Joseph" traces Bernardin's adult life, and, through its tender vignettes, outlines some of the principals that guided Bernardin.

Reading Kennedy, what comes through clearest is that Bernardin was (as are nearly all interesting people), at his core, a contradiction. In his case, it was that a prince of his church was very nearly devoid of ideology. Deeply devout and devoted to his faith, Bernardin was nevertheless always able to see the humanity in everyone, even those with whom he disagreed.

It was this lack of partisanship – rare in the Catholic hierarchy, to hear Kennedy tell it – that allowed Bernardin to serve as an intermediary between the radical Berrigan brothers and the church's old guard. To help forge a working structure for implementing the Vatican II accords in the U.S. church.

And, finally and most humanly, to meet the difficult challenges of his latter years, when he was falsely accused of pedophilia and then diagnosed with terminal cancer.

This is not a biography of Bernardin – there will be time for full-scale examinations of his life and work by others. Rather, this is a literary snapshot of a man, flawed as are we all, but one who enriched our lives, challenged our consciences, and tried to leave the world a better place.